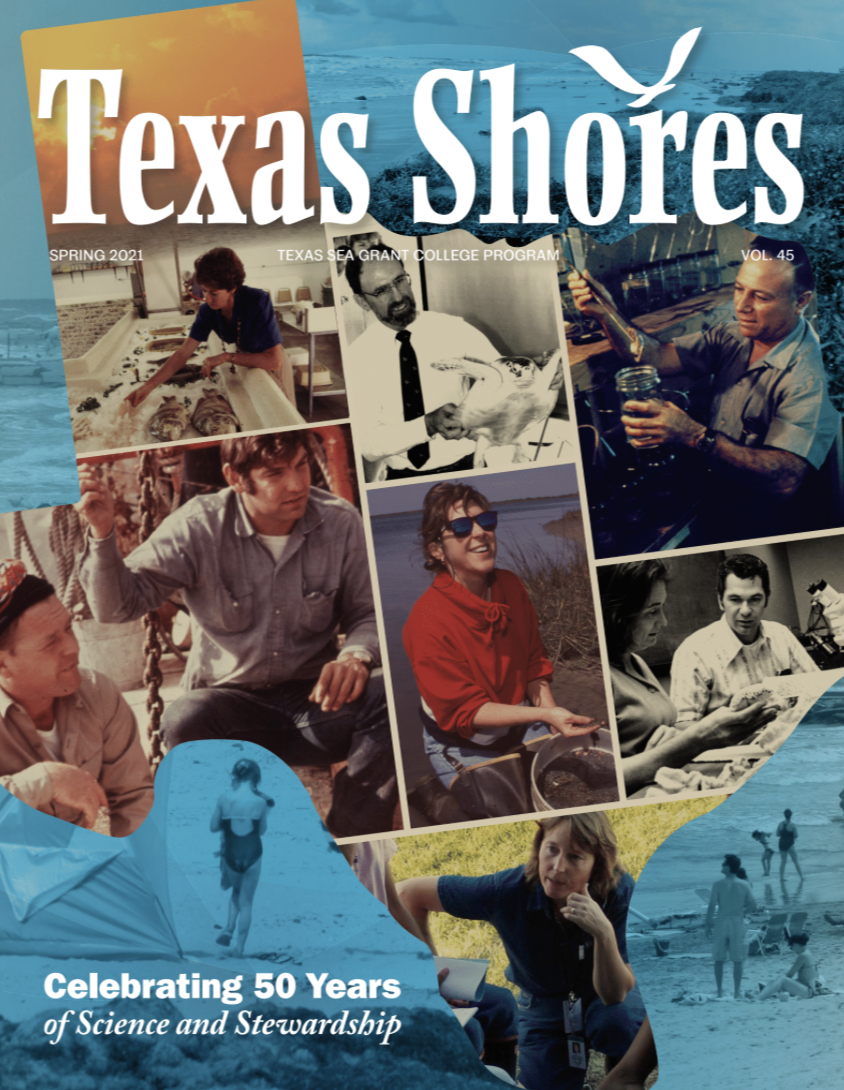

Celebrating 50 Years of Science and Stewardship

As one of the first sea grant programs, Texas Sea Grant has a rich history of supporting the Texas coast and its people through cutting-edge research and innovative outreach and educational programs.

In 2021, Texas Sea Grant celebrates 50 years of science and stewardship. This timeline illustrates a small fraction of the program’s robust history. A more in-depth look at the past, present, and future can be found on display at the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum.

At this exhibit, visitors can discover the wonders of the Texas coast, learn how sea turtles are saved by Turtle Excluder Devices (by walking through a shrimpers’ net), find out how experts build communities for the changing Texas coast, see how Texas Sea Grant has helped these efforts, and more.

The 70s: Explore

The 1970s was a decade characterized by fact-finding and discovery.

Exploring and understanding the ocean became a national conversation. In fact, the National Council on Marine Resources and Engineering Development dubbed it the “International Decade of Ocean Exploration.”

Texas Sea Grant spent its first decade building foundations for its structure, partnerships, and future scholarship. Research on coastal and marine resources, such as seafood, was in its infancy. Texas Sea Grant invested its resources in both short- and long-term projects to support the coast.

AMONG THE FIRST SEA GRANTS

Texas Sea Grant was one of the first four universities to achieve Sea Grant designation in 1971. The other three were Oregon State University, University of Rhode Island, and University of Washington.

JOE SUROVIK IS THE FIRST EXTENSION AGENT

Joe Surovik, Texas Sea Grant's first extension agent

Joe Surovik, Texas Sea Grant's first extension agent

The first extension agent for Texas Sea Grant was Joe Surovik who joined Texas Sea Grant in 1971 to serve Calhoun County.

NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY ACT PASSES

In 1972, researchers (including former Texas Sea Grant director Dr. Tom Bright) went on an expedition to the Flower Garden Banks. This was the same year the National Marine Sanctuary Act was passed.

In 1972, researchers (including former Texas Sea Grant director Dr. Tom Bright) went on an expedition to the Flower Garden Banks. This was the same year the National Marine Sanctuary Act was passed.

In 1972, Congress passed the National Marine Sanctuary Act. This led researchers to advocate for the Flower Garden Banks designation as a sanctuary. The Houston Underwater Club submitted a letter of nomination in 1979 and Texas Sea Grant provided valuable office space for the program in its first year.

TEXAS SEA GRANT’S FIRST DIRECTOR

Texas Sea Grant's first director, Dr. John C. Calhoun Jr.

Texas Sea Grant's first director, Dr. John C. Calhoun Jr.

Dr. John C. Calhoun Jr. was on the first advisory panel of the Sea Grant Program in the late 1960s when it was part of the National Science Foundation (NSF). The panel reviewed university proposals from across the nation to determine where they would award the first Sea Grant money. As the vice president of Texas A&M University at the time, Calhoun resigned from the NSF panel when he decided to make the case for Texas A&M to be an original Sea Grant grantee. He became Texas Sea Grant’s first director from 1968-1972 and again from 1974-1976.

SEA GRANT FUNDS THE SEA AGGIES

Dr. Sammy Ray

Dr. Sammy Ray

Professor Emeritus Dr. Sammy Ray credited Texas Sea Grant’s funding of Texas A&M’s Marine Biology Laboratory as a contributing factor in its development into Texas A&M University at Galveston. Ray’s efforts to include the Marine Biology Laboratory in Texas’ proposal to become a Sea Grant university were also instrumental to Texas A&M’s designation.

Ray, one of the world’s foremost oyster experts, says in a prior issue of Texas Shores, “We received funding for facilities and support for our programs. Texas Sea Grant gave research funds to various researchers doing work in Galveston who used the lab as their headquarters ... I would venture to say that we wouldn’t have what we have in Galveston today if Sea Grant hadn’t come along. Their funding became the core of the marine sciences section of Texas A&M at Galveston.”

THE MARINE ADVISORY SERVICE

The Marine Advisory Service in action

The Marine Advisory Service in action

Research results need to be interpreted and sent to consumers. To do that, Texas Sea Grant created the Marine Advisory Service (MAS) branch. This group was a precursor to today’s extension service. According to Wallace Klussmann, the first MAS program leader, “The Sea Grant philosophy is to do applied research that has meaning to people. Unless we transfer that knowledge or research base to the public, the whole philosophy is not achieved.”

THE MARINE INFORMATION SERVICE

Staff of the Marine Information Service

Staff of the Marine Information Service

With research results available, the issue becomes how to get the information to the public in a usable form. Texas Sea Grant established the Marine Information Service (MIS) to achieve this task. The MIS was staffed with a skilled team of writers and editors who translated the science and information generated by Texas Sea Grant into publications, reports, and educational materials. These include the periodical The University and the Sea,which later evolved into Texas Shoresmagazine.“Our primary job is to take the results of Texas Sea Grant-supported research and make them understandable and available to the people who need the information,” says Laura Colunga, managing editor.

RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

THE EARLY DAYS OF SHRIMP FARMING

When you buy shrimp today, you have options. You can buy wild-caught or farmed shrimp, but that was not always the case. Shrimp farming developed in the 1970s. This new industry meant potential for more jobs, more shrimp, and more profits. However, a number of questions remained before these benefits could be realized. In their demonstration facility, Texas Sea Grant researchers and staff confirmed that shrimp could be produced in natural and artificial ponds. They realized, however, that there were still barriers to shrimp farming’s profitability. The industry needed more scientific investigation to decrease mortality, improve diets, and develop ideal harvesting techniques. One such improvement was the developing a food supply specifically for shrimp raised in captivity. It optimized growth and survival.

The 80s: Innovate

In the 1980s, Texas Sea Grant tackled projects that would substantially improve our understanding of Texas coastal and marine science. Researchers and resource managers found answers to big questions that had long puzzled them, many of which are relevant today.

Texas Sea Grant-funded research spurred innovations in the seafood industry. Their work made shrimp aquaculture more efficient. It made improved marketing practices available to the seafood industry. It also created better and more honest fishing tournaments. These advances positively impacted the seafood industry, recreational fisheries, and the Texas economy.

Other projects also proved to have lasting impacts. Studies of how sea turtles imprint on the beaches they are born on helped scientists understand turtle migration. Research on levels of toxic substances in the Gulf of Mexico informed future regulations of these harmful chemicals.

SAVING SARGENT BEACH

Willie Younger

Willie Younger

The Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW) is a 1,000-mile channel between Brownsville, Texas, and Fort Myers, Florida. The GIWW carries most commercial barge traffic through the Gulf of Mexico. In the 1980s, the waterway risked erosion damage along Sargent Beach in Matagorda County, Texas. If breached, open ocean waves and currents would threaten shipping traffic along the GIWW.

Texas Sea Grant’s Willie Younger recorded erosion levels along Sargent Beach. He alerted authorities to the growing threat to the GIWW. His efforts spawned action from a coalition of agencies, like the Coast Guard, Department of Transportation, and the Corps of Engineers. Their work resulted in the construction of a retaining wall to prevent further erosion of Sargent Beach. The massive wall, 8 feet thick, 7.8 miles long, 30 feet high, saved the GIWW.

“I started contracting the various industries, ports, and other government agencies, requesting financial support to fund a study to document and publish a report on the economic impact of the waterway,” says Willie Younger.

THE YEAR OF THE OCEAN

Director Jennings (left) with Governor Mark White

Director Jennings (left) with Governor Mark White

Texas Governor Mark White proclaimed July 1, 1984 - July 1, 1985 “The Year of the Ocean,” which affirmed the state’s commitment to the ocean and its resources. Texas Sea Grant staff met with the governor. Director Freenan D. Jennings (left in photo) accepted a plaque from the governor.

SAY GOODBYE TO BYCATCH

Gary Graham (left) examining a turtle excluder device

Gary Graham (left) examining a turtle excluder device

The unintentional catch (bycatch) of sea turtles was an issue plaguing the shrimping industry. Balancing the need to protect sea turtles and the ability of shrimpers to operate profitably seemed nearly impossible.

Texas Sea Grant Fisheries Specialist Gary Graham collaborated with fishermen and NOAA scientists to solve this problem. In the 1980s, Texas Sea Grant took an active role in developing and promoting the use of Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs). Graham helped shrimpers around the Gulf of Mexico find, test, and install TEDs and BRDs. His efforts reduced unintentional catch and allowed the smallest amount of shrimp loss.

Graham partnered with Dave Harrington, a specialist from Georgia Sea Grant, and several shrimpers to determine the best TED design that would maximize shrimp catch while allowing turtles to escape. The widespread use of TEDs has proven to be a sea turtle conservation success. The number of turtles killed by shrimping decreased by 68 percent from 1989 to 2009, largely due to the increased use of TEDs.

RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

TURTLES AND OLFACTORY IMPRINTING

Sea turtles lay eggs on the beach where they were born. After traveling the globe, how do they find their birth beach? Scientists suspected that sea turtles might smell their way home via “olfactory imprinting,” or learning the beach’s scent as hatchlings. If true, conservationists could move eggs to safer beaches before hatching to where turtles could nest for generations.

To test this idea, Texas Sea Grant-funded researcher Dr. David Owens and his team studied turtle eggs from Mexican beaches hatched on South Padre Island. After hatching, Owens played a turtle version of Let’s Make a Deal,asking turtles to choose among four doors:

DOOR # 1:South Padre Island seawater and sand

DOOR # 2:Galveston Island seawater and sand

DOOR # 3:Untreated seawater and sand as a control

DOOR # 4:Untreated seawater and sand as a second control

Adult turtles most often chose Door # 1 with water and sand of their birth beach, confirming that scientists could use the sea turtle’s sense of smell to help save them.

The 90s: Re-Examine

New technology in the 1990s opened new avenues for exploring existing areas of research. These advancements led, not just to a stronger understanding of the research, but also to new areas of study.

DNA sequencing allowed researchers to re-examine relationships within wildlife and fisheries populations. New diving technologies allowed researchers to peer into depths of the ocean that were previously inaccessible and unseen. Texas Sea Grant researchers used the Deep Submergence Vehicle Alvin to discover features of the Gulf of Mexico seafloor. New research also sought to identify microorganisms in the ocean and their effects on ocean life and human health. Additionally, Texas Sea Grant researchers used DNA sequencing to better understand the behavior and relationships of popular sportfish.

FLOWER GARDEN BANKS DESIGNATED

One of the several unique fish from the Flower Garden Banks

One of the several unique fish from the Flower Garden Banks

On Jan. 17, 1992, President George H.W. Bush designated the Flower Garden Banks as the 10th National Marine Sanctuary. The sanctuary was expanded in 1996 to include nearby Stetson Bank

A FISHY FAMILY TREE

Dr. John Gold

Dr. John Gold

To better understand fish behavior, scientists realized that they should look to genes when tracking the movements of fish populations. That is what Texas Sea Grant researcher Dr. John Gold and his colleagues did. He was particularly interested in red drum, black drum, and red snapper, three economically important species in the Gulf of Mexico.

For this study, researchers sampled and genetically analyzed fish across the Gulf to see where closely related fish were located. They found that red drum throughout the Gulf are one big, happy family, genetically speaking, which makes sense for this migratory species. On the other hand, black drum move around less. Black drum in one bay may be genetically different from those in a neighboring bay. Nonmigratory red snapper showed the least amount of genetic relatedness to neighboring populations.

RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

DISCOVERIES IN THE GULF OF MEXICO

These dives led Texas Sea Grant-funded researcher Dr. James Brooks and his colleagues to new discoveries in the Gulf of Mexico. Some of our knowledge about what lies beneath the ocean waves can be attributed to the Deep Submergence Vehicle Alvin. Before Alvin, exploration “cruises” were relatively shallow at only 500-800 meters below the ocean’s surface. Alvin was able to observe below 2,000 meters and, in 1990, was taken on 12 dives to study the Gulf of Mexico seafloor. These dives led to new discoveries in the Gulf of Mexico. Here are just a few brand-new observations researchers made with Alvin:• A salt dome on the deep seafloor• Brine seeps• Deep-sea mussels and tube worms• Oil was seepage from the seafloor

2000s: Expand

In the 2000s, Texas Sea Grant broadened its research programs. Historically, research funding went to topics rigidly associated with the ocean, such as fisheries and marine ecosystems. As the interconnectedness of the natural and physical world became more evident, Texas Sea Grant embraced a broader view of ocean research.

In this decade, Texas Sea Grant’s research explored the impacts of hurricanes, natural disasters, and built environments, like cities. Research also looked into improving the speed of data collection. In a world dominated by the internet and new information technologies, researchers sought to collect and disseminate information as fast as possible, or even in real time.

THE CLEAN MARINA PROGRAM

An employee showing a Clean Marinas Program spill prevention kit

An employee showing a Clean Marinas Program spill prevention kit

The Clean Marina Program promoted clean boating and keeping marinas litter free by providing marina, boatyard, and yacht club operators the resources to manage pollution. The program was a joint effort between Texas Sea Grant, the Marina Association of Texas, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

THE FLOATING CLASSROOM

The Karma shrimp boat and floating classroom

The Karma shrimp boat and floating classroom

The 57-foot former working shrimp boat known as the Karma served as Texas Sea Grant’s floating classroom. Texas Sea Grant welcomed students of all ages aboard to learn about wildlife, water quality, marine transportation, and more.

MAPPING THE OCEAN WITH BATHYMETRY

Researchers Dr. Troy Holcombe (left) and Dr. William R. Bryant (right).

Researchers Dr. Troy Holcombe (left) and Dr. William R. Bryant (right).

Can you believe that some of the same geographic features that we see on land, such as canyons, hills, and mountain ridges are present in the ocean?

“Submarine” mapping of the ocean’s terrain is known as bathymetry. As early as the 1950s, scientists were beginning to produce precise maps of the ocean floor’s geography. By the early 2000s, the technology to characterize these features was even more advanced.

Texas Sea Grant-funded researchers Drs. Troy Holcombe and William R. Bryant produced new detailed maps and began standardizing names for these geographic features. Using an agreed-upon set of names is important to help scientists communicate accurately with one another. This information has many practical applications in ocean engineering, naval operations, oil exploration, laying fiber-optic communications cables, and much more.

RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

DISPROPORTIONATELY DROWNING

Between 1960 and 1995, Texas reported 612 fatalities from floods, the most of any state. To better understand how flooding impacts communities, Texas Sea Grant researcher Dr. Sam Brody and his colleagues examined 832 countywide floods in Texas from 1997-2001. The analysis showed that areas with more low-income and minority residents were more likely to experience deaths or injury from flooding. Additionally, the researchers found that deaths happened more often when it rained the day of the flooding than when it rained the day before. This suggests that communities can be caught by surprise when floods appear with little warning, as with flash floods. Communities engaged in public education, mapping, and flood damage reduction (like implementing flood forecasting plans and adjusting building codes) in exchange for reduced flood insurance premiums experience significantly lower incidents of flood-related deaths.

2010s: Connect

Texas Sea Grant continued to expand its areas of research throughout the 2010s. The interconnected nature of humans and our environment allowed scientists to pursue exciting and broader questions. Researchers studied the widespread and long-term effects human activity has on our environment, as well as how the environment affects humans.

Texas Sea Grant continued its tradition of research in fisheries, ocean animals, and marine environments, while taking research projects further. Research moved inland to investigate freshwater that ultimately ends up in the ocean. Other research projects looked at large-scale, future changes of the coastal environment. These studies continue to paint a more holistic view of the Texas coast

HURRICANE HARVEY RESPONSE

Debris following Hurricane Harvey in Port Aransas.

Debris following Hurricane Harvey in Port Aransas.

Following the devastation of Hurricane Harvey to the Texas coast, Texas Sea Grant took an active role in helping communities, especially the cities of Rockport and Hitchcock. Through the Community Resilience Collaborative, Texas Sea Grant and its partners engaged members of these communities to create Comprehensive Plans that will guide the communities’ future development and make them more resilient to future disasters.

IMPROVED SHRIMP FISHING GEAR

Converting the traditional Kaplan propeller to the Rice Skewed Wheel provides an additional 6 percent fuel saving in the shrimp fishery

Converting the traditional Kaplan propeller to the Rice Skewed Wheel provides an additional 6 percent fuel saving in the shrimp fishery

Texas Sea Grant Fisheries Specialist Gary Graham’s research into better hydrodynamic fishing gear helped Texas shrimpers save 2.4 million gallons of fuel, valued at $5.7 million, in 2010. A more efficient propeller design helped shrimpers find additional savings by reducing oil changes and major engine overhauls. Without this gear, many vessels would have been too expensive to operate, which threatened about 200 jobs.

RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT

A LOW-OXYGEN MYSTERY

Even underwater, oxygen is critical for life to survive. However, some places are hypoxic, meaning they have too little oxygen (less than 2 milligrams per liter) to support marine life. Hypoxic conditions have been observed along the Texas coast since the late 1970s. Initially, scientists blamed excessive nutrients flowing down the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico. In the 2010s, scientists, including Texas Sea Grant-funded researcher Dr. Steven DiMarco, linked a hypoxic event to Brazos River flows by “fingerprinting” the oxygen in coastal water and tracing it back to the river. The peak of the event coincided with the largest Brazos River flow ever recorded near its mouth in July 2007. The researchers concluded that the huge pulse of freshwater entering coastal waters forced low-oxygen water to the seafloor.

For details on hours of operation and opening date, monitor the Bush Library website at www.bush41.org